Stem cells delivered in microcapsules speed wound healing

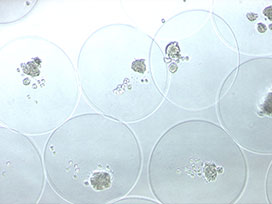

Stem cells confined inside tiny capsules secrete substances that help heal simulated wounds in cell cultures, according to a new study by Baker faculty member Gerlinde Van de Walle and her colleagues. The finding opens up new possibilities for delivering these stem cell products to locations in the body where they can hasten healing.

The capsules need to be tested to see if they help healing in animals and humans, but they could eventually lead to “living bandage” technologies: wound dressings embedded with capsules of stem cells to help the wound regenerate.

“Microencapsulated equine mesenchymal stromal cells promote cutaneous wound healing in vitro” appeared in the April 10 issue of Stem Cell Research & Therapy.

“The encapsulation seems to increase the stem cells’ regenerative potential,” said Van de Walle, adding that the reasons why are not yet known. “It's possible that putting them in capsules changes the interactions between stem cells or changes the microenvironment.”

To her knowledge, Van de Walle said, this is the first time encapsulated stem cells have been used to treat wounds. Her team used horse stem cells and cell cultures because, unlike mice, the healing process in horses shares important similarities with the healing process in humans and because wound healing in horses is a particularly difficult problem in veterinary medicine.

Mesenchymal stem cells are adult stem cells that can be isolated from different parts of the body, and it’s long been known that they secrete substances that aid in tissue healing. Problems arise when trying to use these stem cells in real patients, Van de Walle said, because they often won’t stay put in the healing area and can occasionally form tumors or develop into unwanted cell types. She and her team began exploring the possibilities of encapsulating these cells as a way of avoiding these pitfalls. The capsules help cells stay in place while they secrete substances into the wound and can be removed easily if the stem cells would develop in an adverse way.

The researchers collaborated with Mingling Ma of the Department of Biological and Environmental Engineering and his laboratory to create the coreshell hydrogel microcapsules around the stem cells

Van de Walle says she was excited to see that the capsules did not abolish the stem cell properties but instead appeared to enhance the beneficial effects the stem cell secreted products have on tissue cultures. This suggests that encapsulating the stem cells for wound healing not only avoids certain problems, it can boost the effectiveness of treatment.

With their mesenchymal stem cell work, Van de Walle and her colleagues are trying to understand the basic science behind the regenerative abilities of these cells.

“Currently many equine veterinarians are using stem cells for therapy, but the mechanisms in which they work – and their potential – haven’t been fully explored,” said co-author Rebecca Harman, a graduate student at the Baker Institute. Stem cells can be used in horses without much regulatory oversight, but studies to back up many of these uses are lacking. Van de Walle hopes to shed some light on an area that is poorly understood.

This new work shows microencapsulated stem cells have a great deal of promise, said Harman, but there’s a lot to do before they could be embedded in bandages and used in hospitals or veterinary clinics. Since skin is a complex organ, the approach needs to be studied in a variety of cell culture systems before testing on humans or horses.

“Going in vivo is the ultimate goal, but there’s still work to be done in vitro. We're expanding our cell culture experiments to include other cell types present in skin,” Harman said.

This story originally appeared in the Cornell Chronicle.