Symposium Delves into Public Health Issues

Earth.jpg

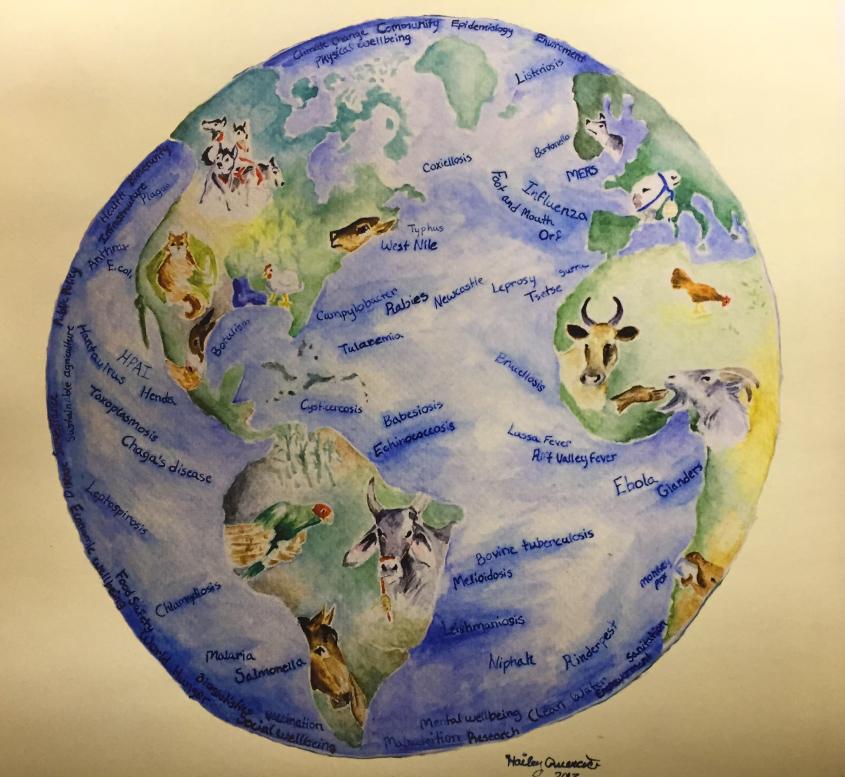

At the eighth annual Veterinary Public Health Symposium, held Sept. 8 and 9, a series of lectures and panel discussions linked veterinary medicine to a range of global issues, from food system security to infectious disease to domestic abuse. The event was organized by the student-run Veterinary Public Health Association and attracted both those affiliated with CVM and local community members.

Cornell veterinary students know that their DVM degree can lead to a rewarding and exciting career. Last weekend, they learned that it can also help solve world problems.

At the eighth annual Veterinary Public Health Symposium, held Sept. 8  and 9, a series of lectures and panel discussions linked veterinary medicine to a range of global issues, from food system security to infectious disease to domestic abuse. The event was organized by the student-run Veterinary Public Health Association and attracted both those affiliated with CVM and local community members.

and 9, a series of lectures and panel discussions linked veterinary medicine to a range of global issues, from food system security to infectious disease to domestic abuse. The event was organized by the student-run Veterinary Public Health Association and attracted both those affiliated with CVM and local community members.

“One goal of the conference was to increase the profile of veterinarian public health,” said Nicholas Roman ’19, outgoing President of the Veterinary Public Health Association. “It’s written in the veterinary oath that we have a duty to promote public health but I don’t know if everyone realizes that or consciously thinks about that.”

Leanne Jankelunas ’20, the incoming President of the group, said another objective of the symposium was to focus on planetary health. “To solve huge problems in our world, we need to include and unite different disciplines,” she explained. “For example, veterinarians deal with wildlife medicine and endangered species, and that impacts the environment, which affects human population. It’s the idea of the spider web—everyone is interconnected, and if you break a little bit of that chain, something else breaks, and then another thing breaks.”

The symposium began Friday night with the George C. Poppensiek Lecture in Global Veterinary Medicine, given by Dr. W. Ron DeHaven, DVM, MBA, recently retired CEO of the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA). Titled “Veterinarian Medicine: A profession in transition (or is it in transformation?),” the talk disseminated discussions he had with 11 thought leaders in the profession as well as his own personal insights. He cited the current challenge connected to the loss of public trust due to the rising costs of care. “We need to realize that not everyone can or is willing to pay for premium care,” DeHaven said. “I think we’ll continue to see the emergence of lower cost models.”

DeHaven also relayed where the profession is growing, which includes work in lab animal medicine research, pharmaceutical and food companies, public and government entities, and the military. Opportunities on the horizon for students include preventive pet care and global food animal production. He encouraged students to not have a self-limiting mindset. “Don’t think of yourself as only a veterinarian, but rather, ‘As a veterinarian, I bring these qualities to the job,’” he said.

Saturday morning kicked off with lectures and a panel focused on mental health. Presenters included Dr. Greg Eells,  director of counseling and psychological services at Cornell; Frank Kruppa, MPA, public health director at Tompkins County Public Health; and Dr. Lila Miller ’77, vice president of shelter medicine at the ASPCA.

director of counseling and psychological services at Cornell; Frank Kruppa, MPA, public health director at Tompkins County Public Health; and Dr. Lila Miller ’77, vice president of shelter medicine at the ASPCA.

Miller offered insights into the connection between veterinary medicine and public health as it relates to animal abuse. She explained the interrelations among animal abuse, child maltreatment, elder abuse, and domestic abuse. In one study cited, 59 percent of women who had been abused remained in their living situations due to fear of safety for their pets.

“When animals are abused, humans are at risk,” Miller said. “And when humans are abused, animals are at risk.”

She went on to outline the role of the veterinarian in handling animal abuse and how it’s not just an animal medicine problem but a social problem. “You have to deal with the underlying issues such as family and community,” Miller explained. “This is hard to do.”

The second panel of the day zeroed in on planetary health, and began with a lecture by Dr. Steven A. Osofsky ’89, Jay Hyman Professor of Wildlife Health & Health Policy that offered a synopsis of ecological problems related to the increasing human population and its consumption patterns, and relayed how his research has recently taken a transformative turn through building new partnerships.

“There’s no mystery in what’s happening to our environment, but our research and arguments on how this is harming wildlife were not leading to policy changes,” Osofsky said. “However, when we started to talk about how this affects public health, people started listening. We saw that the conservation community must be able to speak to the public health community to enact real change.”

Another new approach has been sitting down with decision-makers and finding out what they need before embarking on specific studies. “Research needs to be policy-focused from the start,” Osofsky said.

Dr. Hussni O. Mohammed, professor of epidemiology at the College, delved into the progress and setbacks of the One Health movement. For a project on assessing the risks of the absence of filtration in New York City’s water supply, Mohammed put together a diverse team of experts. “It’s important to take a multi-disciplinary approach to risk management,” he said.

The third speaker, Dr. Karyn A. Havas, senior research associate with the Masters of Public Health and International Programs at the College, spoke about how the efficiencies in the swine industry can more easily lead to disease outbreak. “The quest is to find a balance between economic objectives and biosecurity systems prior to a trade-limiting disease outbreak,” she said.

Havas explained that the current swine industry frequently transfers pigs, which enables a small number of animals to rapidly infect others. “One million pigs are born in North Carolina every day,” she said. “Half of them go to Iowa, and then a large number of them might eventually go all the way to Hawai’i to be slaughtered. There are 600,000 pigs on the road every day. Every year, 23 million pigs are brought to Iowa.”

While leading the USDA’s Diagnostic Services Section in the Foreign Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory, Havas encountered a new virus in pigs that was first seen at a farm in Ohio in 2013 and spread to many farms across the nation by 2016. "We found the source to be shipping containers of food from China," she said. "The transport trucks were infected, and so soon were the collection points, and it easily spread from farm to farm.”

The final panel focused on herd health beginning with Dr. Elizabeth Bunting, senior extension associate with the Department of Population Medicine and Diagnostic Sciences, and her presentation, on Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD). Related to mad cow disease, CWD (also called prion disease) was first identified in the American deer population in 1967 has slowly spread without much notice. Bunting’s work is uncovering that CWD’s danger to humans may be greater that previously thought.

She explained that it may be possible for prions to remain in the soil for 20 years, and that they can get into food grown in that soil, such as wheat and tomatoes. A very recent study not yet published found when macaques were fed infected deer meat, they became infected with CWD.

Dr. Elizabeth Berliner, Janet L. Swanson director of shelter medicine with the Maddie’s Shelter Medicine Program., detailed her work in shelter animal medicine, which DeHaven had talked about the previous evening as a growing field. With large discrepancies in how shelters operate across the country, Berliner is working on designing specific protocols for intake, outtake, and care.

Dr. Elizabeth Berliner, Janet L. Swanson director of shelter medicine with the Maddie’s Shelter Medicine Program., detailed her work in shelter animal medicine, which DeHaven had talked about the previous evening as a growing field. With large discrepancies in how shelters operate across the country, Berliner is working on designing specific protocols for intake, outtake, and care.

“You have to make choices for individual animals related to how it affects the herd [all the animals at the shelter] and choices for the herd balanced with how it affects individual animals,” she said.

Berliner also spoke about how protocols do not just affect the animals in a shelter, but also the surrounding community. “One in six people live in poverty,” she said. “Pets also live in poverty. A big question is: How do we allow access to veterinary care for those in poverty?”

Dean Lorin Warnick spoke about the critical role veterinarians play in ensuring the quality and safety of our food supply. He offered a history lesson on regulations related to food safety and a theory presented in the book Arresting Contagion about how disease control was a large factor in shaping the federal government.

Dean Warnick looked specifically at bovine tuberculosis and salmonella, explaining how livestock disease control requires collaboration and organization—and that it always has. In 1903, it was Cornell veterinarians who uncovered the infected water sources during a salmonella outbreak in Ithaca.

He also relayed how working with food systems can offer a rewarding path for DVM students. “It has numerous links to public health and there are a lot of career opportunities in it,” Warnick said.

Panel discussions followed each of the focus areas sessions. A topic that resurfaced several times during these discussions was the role of protein in food consumption. “One of the more controversial topics was the idea that protein is possibly not as important as we have thought,” said Roman. “At last year’s Poppensiek lecture, the speaker [Dr. Thomas W. Graham, president and CEO for Veterinarians Without Borders] talked about how you can’t feed the world with beans. Today we heard the opposite idea and that sparked a lot of great discussion. Some veterinarians see their role being to help the farmer feed the world, but it’s interesting to think about the cost margins on keeping food affordable versus preventing other public health issues associated with animal agriculture.”

By Eleanor Frankel