Student blog: Treating wildlife in Costa Rica

Costa Rica makes up only 0.03% of the surface area of the earth but is home to an incredible 6% of the world’s biodiversity. With this remarkable wealth of wildlife, unfortunately comes conflict with humans and domestic animals and the need for wildlife rescue centers. This past summer, thanks to funding from Cornell’s College of Veterinary Medicine Expanding Horizons program I traveled to Puerto Viejo de Talamanca, a beautiful beach town along the Caribbean coast of Costa Rica, to work with Dr. Roger Such at the Jaguar Rescue Center. The center was founded in 2008 using the nickname bestowed on its founders by the local community in honor of one of its first patients. Since then, the center has an impressive record of successful medical treatment, rehabilitation and release of species ranging from sloths, kinkajou and howler monkeys to toucans, iguanas and sea turtles. Over the course of my two-month internship, I participated in the medical care of just a small percentage of the over nine-hundred animals that the center takes in annually.

Helping sloths heal

One of the most common reasons that wildlife come to the hospital is electrocution. Most electricity lines in Costa Rica are not insulated, resulting in thousands of animals being electrocuted annually. To reduce electrocutions the center started The Shock Free Zone program, which raises funds to insulate power lines and install wildlife canopy bridges. Hopefully this program will prevent cases like the two-toed sloth Cuca from coming into the hospital. When Cuca arrived only a few days into my internship, I saw firsthand the devastating injuries caused by electrocution. The first thing I noticed when the rescue team carried her in was the smell of hair burning. On closer examination it became apparent that the skin and muscle of Cuca’s hands and feet had been burned down until her tendons and bones were visible. On seeing this damage, I quickly lost hope for Cuca’s survival. However, having worked on hundreds of electrocuted animals, Such has seen that sloths have an incredible ability to heal and can regain the function of horrifically injured limbs. Therefore, after an initial assessment and stabilization, he moved forward with an amputation of Cuca’s left arm at the elbow. Meanwhile, the wounds on the rest of her limbs were treated and bandaged with honey to encourage healing. For the remainder of my internship, we changed these bandages every other day, which allowed me to see Cuca’s incredible healing process. Six weeks after she arrived literally smoking, the wounds on Cuca’s hands were closing and she was starting to grip and eat on her own. Cuca has a long medical and rehabilitation journey ahead of her, but previous patients have proven to be incredibly adaptable and resilient in learning to climb after losing a limb. Sloths released with three limbs that have later been identified using microchips have shown themselves to be successfully rewilded. I am hopeful that one day Cuca will be able to join these center alumni in the jungle.

Another two-toed sloth that I worked with was Marte. When I arrived at the hospital, Marte was already a long-term, much beloved, hospital resident due to a recurring abscess near the left armpit. Unfortunately, it was clear from Marte’s low energy, poor appetite, and bloodwork that his body was losing to the infection. Without access to bacterial culture and sensitivity testing in Costa Rica, we had to adopt a multipronged approach and rely on Such’s extensive experience. He assessed the extent of the abscess using ultrasound and then manually removed as much of the abscess fluid as possible, placed a drain surgically, and started an aggressive round of antibiotics. Remarkably, within a week of this procedure Marte became more active and started gobbling up his veggies and leaves again. Marte’s story was an example of how wildlife veterinarians, especially those working in the non-profit realm, are able to overcome challenges with innovation, experience and high-quality medicine.

Giving the greatest chance possible

Another example of the veterinary team’s excellence was the case of Scrat the opossum, who arrived with an infected wound on her hip, paralyzed hindlimbs, and her pouch full of six babies. Intensive wound care resolved the infection, and, thanks to Scrat’s medical and nutritional treatments, her babies were able to develop into healthy joeys and be released. Due to her persistent hindlimb weakness, Scrat remained in the clinic long after her joeys entered the jungle. Instead of writing Scrat off as an unreleasable case, we started an intensive rehabilitation program that included modalities more commonly used for companion animals than for wildlife. I am a huge fan of opossums, so I volunteered to conduct Scrat’s physical therapy sessions, which consisted of massaging her atrophied muscles, gently moving her hindlimb joints through their full range of motion, and even conducting laser therapy. While Scrat had yet to show significant improvement by the time I left, I feel proud to have participated in her care. Furthermore, it was inspiring and fulfilling to have been part of a team that invests so much time and effort into giving each animal the greatest chance possible at returning to the wild

Our next patient, Vecna the kinkajou, was attacked by a dog and had severe facial wounds. As in the United States, conflict with domesticated animals is a common cause of wildlife injury in Costa Rica. Vecna’s wounds required emergency reconstructive surgery. Unlike in companion animal medicine, the goal of this surgery was solely to restore function, not beauty. After the surgery, Vecna started eating well and displaying the typical feisty, curious kinkajou behavior during treatment sessions. About a week after I left the center, he was able to be moved into a large enclosure outside the hospital, which was the first step in his rehabilitation training. Once he has shown himself to be wild-ready, Vecna will be released at the La Ceiba Natural Reserve. These 490,000 square miles of primary forest has been set aside as protected land through the efforts of the center and is connected to an extensive natural biological corridor that runs through Costa Rica and Panama. Preserving the natural habitat of Costa Rican wildlife is a key component of the center’s conservation impact.

Working through despair, finding the joy

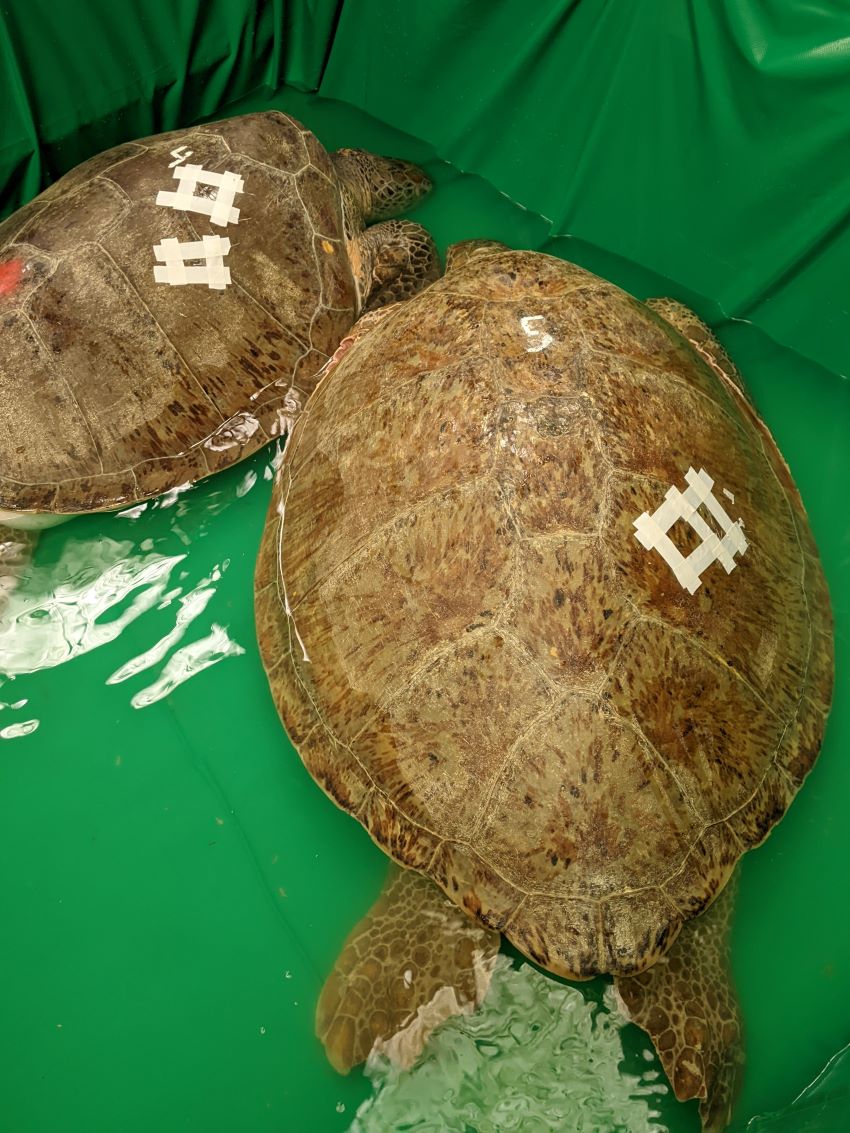

Working at a wildlife hospital means that at any point your plan for the day may be completely changed by the arrival of a new rescue. A dramatic example happened during my fourth week at the center when the police showed up with thirteen confiscated green sea turtles with harpoon wounds. This was a logistical challenge for many reasons, not least of which was the fact that the center did not have any pools for the turtles. As the veterinary team worked to clean and assess the harpoon wounds, the grounds team achieved an incredible feat, building five pools from scrap metal and tarp, and moving thirteen four-hundred-pound turtles into them. For the rest of my internship, a block of time each day was dedicated to treating the sea turtles. This was a laborious process of removing necrotic tissue and shell debris from the harpoon wounds, filling the wounds with honey, and taping clingwrap bandages in place. Turtles that appeared lethargic and had wounds that were deep enough to connect to the body cavity were also given antibiotics and fluids.

At times I would pause during this process and, looking out at the crowded pools, the magnitude of the devastation caused by the poachers would hit me all over again. The despair at the damage humans have caused was countered by the joy I felt when the first turtles were able to be released about a week after their arrival. Watching the turtle disappear into the waves from the beach, surrounded by other center workers, tourists, and Puerto Viejo locals, was one of the highlights of my veterinary experiences.

These five stories are only a few of the cases that I had the privilege to work on this summer. I left the Jaguar Rescue Center after eight weeks having grown as a veterinary professional and person. I am incredibly grateful to the Jaguar Rescue Center and Dr. Such for being such an inspirational and generous model of truly impactful, compassionate and skilled wildlife medicine. As I continue my veterinary education, I will carry the knowledge and inspiration that I gained at the Jaguar Rescue Center with me.

Sophie Yasuda is a D.V.M. candidate, class of 2025, at Cornell CVM. She is passionate about wildlife medicine and using rescue, rehabilitation, and release to conserve wild populations. She works as a student technician at Cornell’s Janet L. Swanson wildlife hospital.

All photos by Sophie Yasuda